A Day in the Life of Future Pilgrim

- Josiah Stowe

- May 21, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: May 21, 2025

The city’s design embodied its theology. Courtyards opened toward the morning sun; to the east. Stone and timber bore the weight of generations. Psalm fragments adorned the gates. All real property was held in hereditary trust. Public power was limited. Each household was its own economy, tied by tithe, bound by love, and disciplined by the church. Each sphere operating according to God's law.

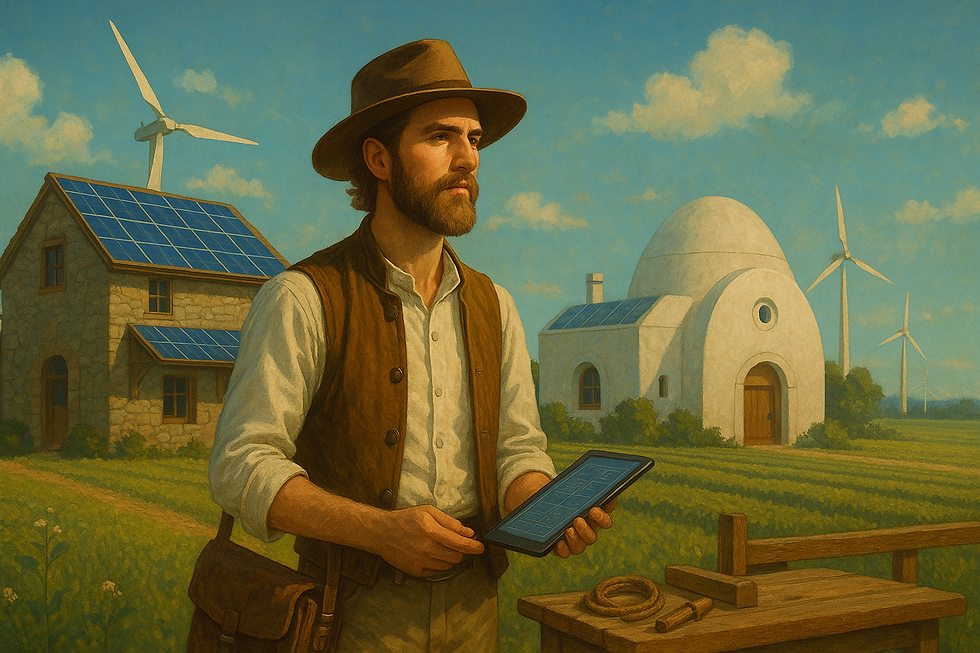

The sun rose quietly over the fields, casting golden light on rooftops lined with solar arrays and trellises heavy with fruit. The air was crisp, carrying the scent of tilled earth and blooming herbs. Future Pilgrim awoke as he did each day, with prayer, thanksgiving, and an eye toward dominion. His home, constructed by his great grandfather and restored with modern materials, stood on land titled in trust, held within the family line, protected from seizure and speculation.

The household stirred. His eldest son, Levi was of working age so he tended the beehives and monitored the vineyard’s irrigation system via a handheld console. The younger children prepared for their lessons: Scripture, mathematics, Mosaic rhetoric, and the mechanics of trade, taught through a hybrid of handwritten materials and a locally hosted library of recorded lectures. Guild alliances developed curriculum rooted in Scripture and practice, and was overseen by household elders.

Selah, Pilgrim’s wife, managed the family’s cooperative ledger using a tablet running decentralized software. She organized distribution routes for leather goods, sourdough starter, woven satchels, and iron fittings, with orders arranged through the city’s encrypted market grid. Pilgrim took a few minutes and reviewed the week’s orders while drinking coffee he had cultivated in their greenhouse. They did not aspire to luxury, only fruitfulness. Their tools, their means, and their time were stewarded together, not hoarded. Their wealth was purposed for familial productivity, not vain comforts.

Pilgrim donned a locally woven tunic and stepped into his workshop. Amos, his second-born, was shaping a gear for their windmill on a CNC machine, guided by a template from a communal design archive. Most households in New Bethsaida contributed to or borrowed from this archive, hosted on peer-linked terminals across the city. After a few hours of shaping metal into useful tools and toys, they had fulfilled all of the orders for the day so they closed up the shop to enjoy the rest of their day.

In the open-air marketplace, Pilgrim passed vendors exchanging soap for thread, books for produce, and wool for lamp oil. Where direct bartering was less feasible, transactions were facilitated with pure precious metals or stones of calibrated weights and cuts. Touchstones for verification existed, but were rarely necessary. The economy relied on truth and trust. Digital exchanges facilitated long distance trading and were authenticated via tokens called SongCoins, cryptographically secure but still morally intelligible. Each trade was publicly accountable, visible to and verifiable by everyone. A modest solar rig powered a small server in the market for that occasional digital exchange and for emergency comms. No central power grid was necessary.

Passing by the food stalls, Pilgrim saw a widow accepting her daily fresh bread from a bakery, her account subsidized through the diaconate. Deacons tracked these needs through family reports, so charity was interpersonal, not anonymous. Needs were known and met with abundance. In a society this productive, those who could not be economically productive were not resented. True wealth is when there is always more than enough food to go around.

Pilgrim was due at the at the Council House, a huge timber-framed and masonry-rooted building, bearing engravings on the lintels from Isaiah and Deuteronomy. The elders, fathers and craftsmen, gathered to review a land inheritance transfer prompted by a betrothal that involved a family from a neighboring city. The dispute was examined in light of biblical law, the tribal ledgers, and verbal testimony. The matter was resolved promptly with prayer and consensus. The Word of God was the only final appeal. The Chapel stood across from the Council House, at the exact center of the city, blindingly white in the early afternoon sun. It's limestone spires were New Bethsaida's tallest structures, over 30 cubits high, reaching to heaven and pointing the people to God. The stained glass windows were elaborate, masterfully crafted over decades. They told the stories of Scripture with such clarity that even the illiterate would be left without excuse. Even though Pilgrim had attended Sunday services, weddings, and funerals there all his life he caught himself staring at it's architecture as he walked out toward home.

Later in the afternoon, since he had some free time Pilgrim called a household meeting and reviewed the economic report for their foundry with his oldest sons. The forge ran on biochar and the bellows used a waterwheel as was standard practice, but they brought in a surfacing mill recently which drew a lot of electric power. Total output had increased, but the energy efficiency needed improvement. Amos proposed a new solar array for the roof to offset the increased electric consumption. Levi seconded the motion. They all agreed to install the solar array next quarter with Pilgrim formally making the decision and recording their minutes on digital minute book attached to the community blockchain. All business was covenantal and stewarded carefully since everything they owned belonged ultimately to God.

As the sun began to set, Pilgrim and his youngest son, Asher, walked the perimeter of the community orchard, bountiful due to the Salatin permaculture. They pruned where necessary, ate some fruits that ripened too early, gathered wildflowers for Selah, and talked. Asher asked if he could paint some rocks gold and use them to buy some toys. Pilgrim knelt beside him, quoting Leviticus and Proverbs on honest measures. “A false balance is an abomination,” he said. “God sees the hand and the heart.” Asher nodded, remembering his catechism.

As night fell, the family gathered. They sang psalms by the firepit, accompanied by a stringed dulcimer Amos had built. On the recommendation from a friend, they watched a sermon from the faraway town of Antioch on a local file-share device; it was an exposition of Isaiah’s vision of nations streaming to the mountain of the Lord. Pilgrim closed his eyes in quiet joy. Outside the covenant settlements, the shrinking old world still labored under true scarcity, debt, and deceit. If only they would submit to the Law of the Lord, they too could be free.

After worship and dinner, Pilgrim lay beneath a roof of copper and cedar beside his wife, watching stars through a clear solar-glass pane, the occasional notification of an astronomical event swiped away with a gesture. The heavens declared God’s glory. The earth, under faithful hands, was being subdued. Technology served as a tool, not a master. The law of God shaped even the circuits. The world was changing. Quietly. Steadily. Through families, through churches, and through men like Pilgrim.

And tomorrow, there would be more work to do.

Comments